Young people's mental health

How healthcare providers and charities can work together to deliver interventions that have a lasting impact on young people.

How healthcare providers and charities can work together to deliver interventions that have a lasting impact on young people.

In March 2023, a young person's mental health service made contact with us at Dogs for Good. The service, an 18-bed in-patient unit forming part of Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust, is a Tier 4 service - meaning it supports the needs of young people with the most complex, severe or persistent mental health problems, including mood disorders, eating disorders and psychosis. Many have also experienced attachment difficulties and trauma, and some have a diagnosis of autism.

"One of the biggest challenges we face is keeping young people in touch with the outside world while they’re in the unit,” says the Project Lead and Senior Occupational Therapist (OT). “That engagement is crucial to their recovery.”

The unit had been actively seeking a charity partner to work with, but was struggling to find the right match, partly due to a lack of third sector resource post-Covid, and partly because of the particular challenges involved in working with young people with such complex needs.

The drive to work with animals came from the young people themselves. "We check in regularly with the young people to talk about what’s going on on the ward, and what new things they’d like to try," says their Senior OT. “They brought up the idea of a Pets As Therapy or PAT dog. Having had animals on the unit in the past, we were aware of the potential benefits, so we decided to go down that route."

[The service] had an open mind about how this could work and a willingness to explore different ideas and see where we could achieve the biggest impact.

For the unit, the initial priority was to support young people to get out into the community, with the goal of easing the eventual transition back to their family and home. The unit’s OT team worked closely with our Community Dog team to design a programme made up of two strands:

Dogs for Good Development Officer Victoria Maclennan-Jones supported the pilot sessions, along with Community Dog Ursa. “Ursa’s a really charismatic, friendly dog,” Victoria says. “She wants everyone to get involved. But she’s so calm and empathetic as well. That’s why we thought she’d be perfect for the pilot.”

Each session was carefully designed to provide a range of opportunities to develop skills, for example team working and communication. “For some of the young people, leaving the unit was difficult,” says Victoria. “Focusing on the dog really helped with that. It also helped the young people to think about each others’ needs – we only went out if everyone felt comfortable. Otherwise, we’d stay in the unit and do something else.”

Activities such as setting up an agility course or the ever-popular dog bingo proved a relaxed way of encouraging and reinforcing positive behaviours: planning, team working, taking turns and open communication. At the drop-in sessions young people were also free to just sit with Ursa, stroking or brushing her.

Flexibility was key and that’s what you get with a dog. They’re so quick to adapt. Plus there’s no pressure, no expectation. For these young people, that meant they could let down some barriers, knowing they wouldn’t be judged. And everything can happen at their own pace.

At the end of the pilot phase, colleagues from the unit and Dogs for Good got together to review what had worked and what could be improved. The message was clear: young people had benefited from the interaction with Ursa and there was strong demand for more of them to be able to join in.

“Staff were seeing changes in the patients attending the drop-in sessions,” says Selina. “They were engaging in activities they wouldn’t engage in normally. We thought if we structured things in a different way, we could make the sessions accessible to more young people.”

Dogs for Good and the project team decided together that all sessions would be held at the unit, with no restriction on numbers, and that they should be linked to the work of the education unit.

“Education can be challenging for these young people,” says their Senior OT. “They might have had difficult experiences in the past, and many have been out of education for a long time. The idea of working with a dog was such a powerful motivator, we wanted to explore how we could use it to re-engage them in an educational setting.”

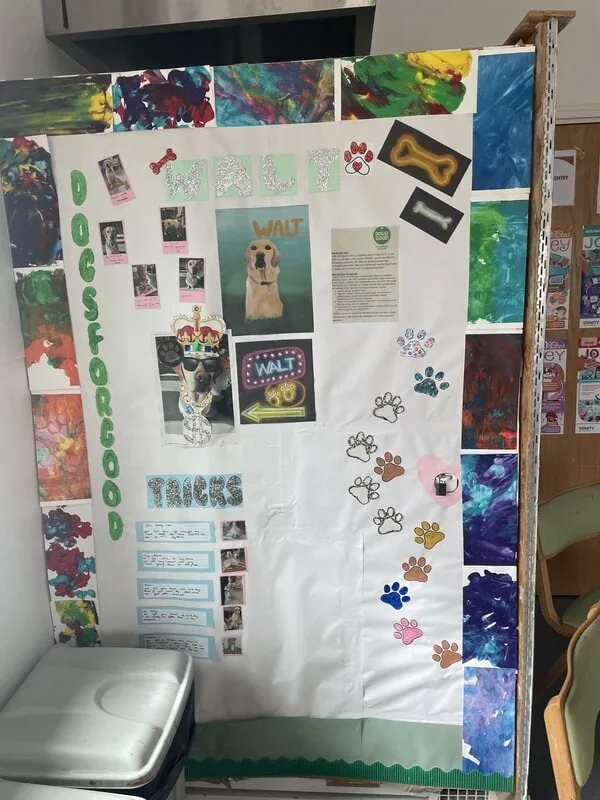

This time, the sessions were ran with Community Dog handler Sarah and Community Dog Walt. Using the education unit’s art room, the activities aimed to encourage planning and team working, and support better communication and interaction between the young people.

Engaging with the activities helps them to think of themselves as having an identity beyond being a patient in a mental health unit. They’re a helper. A dog handler. A student. It gets them thinking about what else they could do with their lives. It’s a really powerful shift.

In addition to the weekly group sessions, Sarah and Walt were also able to provide one-to-one support for individual patients, for example taking them out for a 20-minute walk around the grounds.

“The move to the education unit didn’t mean we’d given up on the idea of getting young people out and about,” explains Selina. “There’s still value in that. It’s just looking at it in a more individual way. What’s really important is being able to provide a flexible service that can respond to need on the day. You’ve got to have different options, so it feels seamless for the young people.”

The impact of the project has been overwhelming positively. Young people are interested and engaged and our dogs have helped to make the idea of school less scary and intimidating - leading to more positive associations around the education unit and improved attendance.

Staff also reported a reduction in incidents on the unit at the times when Walt and Sarah were there. Young people have been supported to open up and communicate, too.

“We would see changes in engagement, motivation and mood that would last throughout the week,” says their Senior OT. “Even when Walt wasn’t there, he was having an impact. Staff in the education unit could design activities around him, or even just encourage the young people to talk about what they’d done with him the previous week or what they were going to do next. It brought a change to them that was really lovely to see.”

The project team has also seen a positive impact on relationships, with Walt supporting increased engagement between the OT team and education, nursing and medical colleagues, and also between patients, staff and their families.

Positive impacts for individual patients include:

A survey carried out by the project team in summer 2024 found that all 17 staff in the unit were keen to continue working with Walt and Sarah, citing the young people’s improved mood and motivation as well as a boost to staff wellbeing.

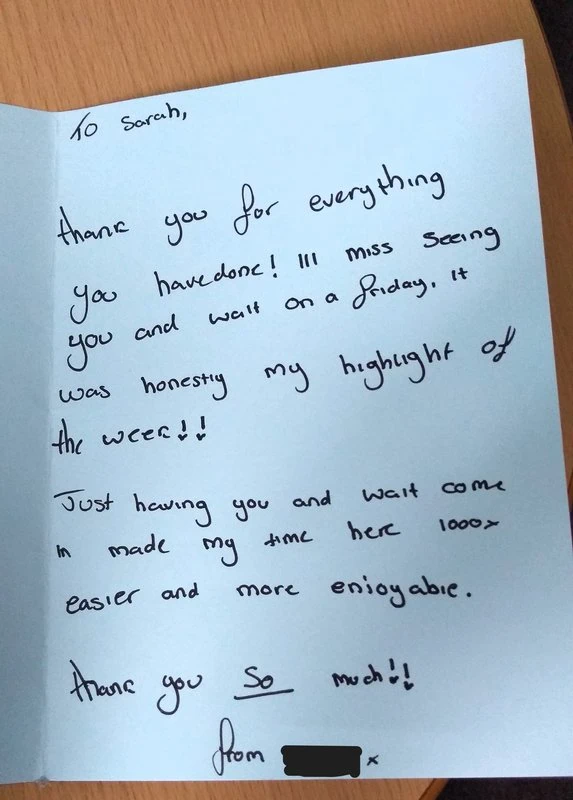

This was reflected in the responses from young people themselves, with them all agreeing that taking part in sessions with Walt and Sarah improved their mood, motivation and engagement. When they were asked what could be improved, they suggested seeing Walt more often and having more opportunities to spend time with him one-to-one.

The sessions ended in June 2024, but Sarah and Walt have continued to run drop-in sessions at the unit and have even extended their work to another unit, supporting and creating special connections with clinically vulnerable young people.